Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD)

What is posterior vitreous detachment (PVD)?

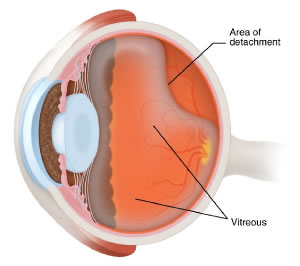

It is a normal event that occurs in about 2/3 of people by the age of 60. The vitreous (the gel that fills the back portion of the eye) is quite firm at birth — like Jello — but gradually becomes more liquefied with age. As it liquefies, it eventually separates from the retina, from back to front. Although the vitreous is a gel, it actually has a “surface” that we call the “hyaloid”. The hyaloid is the portion of the vitreous that is in contact with the retina at birth and separates from the retina when PVD occurs. The diagram to the right shows a developing PVD:

It is a normal event that occurs in about 2/3 of people by the age of 60. The vitreous (the gel that fills the back portion of the eye) is quite firm at birth — like Jello — but gradually becomes more liquefied with age. As it liquefies, it eventually separates from the retina, from back to front. Although the vitreous is a gel, it actually has a “surface” that we call the “hyaloid”. The hyaloid is the portion of the vitreous that is in contact with the retina at birth and separates from the retina when PVD occurs. The diagram to the right shows a developing PVD:

What symptoms result from PVD?

PVD often goes unnoticed, but it can cause alarming symptoms. Many people who develop PVD notice flashing lights and “floaters”. The flashes often resemble lightning bolts in the peripheral vision. They are the result of tugging by the hyaloid on the retina as it separates. As the PVD develops, the hyaloid separates from back to front. Eventually, the separating hyaloid reaches the “vitreous base”, where the vitreous is strongly adherent to the peripheral retina. The vitreous base cannot separate from the retina, except in cases of severe eye trauma. When the separating hyaloid reaches the vitreous base region, it often exerts traction on the retina. Whenever the retina is physically stimulated, as in tugging by the separating vitreous, it senses light. Hence, the flashes. These flashes are most often noticed in the dark and usually subside after a few months.

The floaters are sometimes described as “squiggles” or “dots” floating around in the vision. Some patients notice a “ring”, or a portion of a ring, floating in the vision. This ring typically represents the portion of the hyaloid that was once adherent at the edge of the optic nerve, which is circular. If that ring remains intact after the hyaloid separates from the retina, it can be visible to the patient.

What problems can result from PVD?

PVD usually results in no more than some annoying and potentially alarming symptoms — flashes and floaters. However, the separating vitreous can sometimes cause enough traction on the retina that the retina tears. A retinal tear is analogous to cutting a hole in wallpaper. Just as you could theoretically stick your hand through a hole in the wallpaper and pull it off the wall, the vitreous (which is mostly water) can migrate through a retinal tear and get behind the retina. When the retina separates from the wall of the eye, you have a retinal detachment, which can threaten the vision and must be repaired surgically.

Is there a treatment for the floaters that result from PVD?

Retina specialists typically recommend against treatment for floaters. Although they can be quite bothersome shortly after their onset, they usually subside over time. Patients with PVD usually have more floaters than before the PVD, but the floaters rarely remain bothersome in the long term. A very small fraction of patients find their floaters to be persistent and almost debilitating. These patients often complain that the floaters are located precisely where they need to focus, and they usually describe difficulty with reading and driving. In such rare cases, vitrectomy surgery can be helpful. However, vitrectomy does involve small but real risk, so we at Iowa Retina discourage surgical intervention. If the floaters remain extremely bothersome over time and the patient remains motivated to proceed with vitrectomy after being carefully informed of its risks, there can be a role for surgery. Patients who do undergo vitrectomy for severely symptomatic floaters are often very appreciative after surgery, but they must be very carefully selected and thoroughly informed that the procedure is not without risk.